Proponents tout Kratom, a popular herbal substance of Southeast Asian origin, as a potentially life-changing pain reliever that can help those hooked on opioids kick their dangerous habits. Other users claim that kratom is also addictive and suggest that its effects are nearly as problematic as the narcotics they’d been trying to leave behind — which explains why it continues to be targeted by the federal Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA has even taken part in the seizure of a shipment bound for Denver, where the city’s health department banned kratom for human consumption in late 2017. But despite such actions, the herb is currently selling by the ton in Colorado.

So is kratom a miracle drug that could follow the trail toward greater acceptance blazed by medical marijuana? Or will it trigger a countrywide crackdown that could drive the product underground?

The man most likely to provide the answers to these questions is Christopher McCurdy, a professor of medical chemistry for the University of Florida College of Pharmacy. If there’s one person in the United States who’ll determine whether kratom remains in the legal shadows in this country or becomes a fully regulated substance whose sales are authorized from coast to coast, it’s him.

Why? Since December 2018, McCurdy’s UF institution has received two grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse totaling $6.9 million to study the various effects of kratom and its alkaloids, and McCurdy is the lead investigator in these analyses. If his findings suggest medical efficacy, additional research of the sort that could result in an eventual blessing from the feds is all but assured. But should he and his colleagues determine that the risks outweigh the benefits, the movement to mainstream kratom may well be doomed.

Marijuana Deals Near You

At this point, McCurdy, who rarely gives interviews, isn’t tipping his hand in terms of which way he’s leaning. “Right now, our approach is, ‘Let’s get the science. Let’s see what it tells us,'” he says. “If science tells us it’s bad news, we’ll definitely report that. But if the science tells us there’s great potential, or some potential, to help those suffering from addiction, we definitely want to tap that and find out as much as we can.”

Kratom advocates believe this verdict is already in. Mac Haddow, senior fellow on public policy with the American Kratom Association, who is currently pitching legislation dubbed the Kratom Consumer Protection Act in Colorado and other states, told us, “The science resonates. The science is so powerful in terms of kratom’s potential beneficial effects, and that it’s safe.”

Still, Faith Day, the founder and co-owner of Lakewood’s Clean Kratom Wellness Center, sees the need for the kind of oversight that could flow from McCurdy’s research. In her words, “There’s just a lot of sketchy players out there. We need the government to be able to work with the kratom community so we can provide safe access to this product. It’s been put in such a bad light because of all of these issues: contamination issues, heavy metals.”

For his part, McCurdy didn’t set out to become the key to kratom. “I’ve been involved for a long time in health care and research,” he says. “I started life as a pharmacist and decided to go to graduate school after I had some research experience in pharmacy school.

McCurdy entered graduate school and worked on treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and nicotine dependence through a natural product called lobeline, he says. “That got me interested in going on and doing a post-doctoral fellowship with a guy named Phil Portoghese at the University of Minnesota. He was one of the fathers of opioid chemistry and really helped to define the opioid systems as we know them today. I learned from him that you can essentially spend an entire year on a molecule or a plant.”

The knowledge of molecular biology and pharmacology and the opioid system made him think that if he could try to come up with drugs to treat dependence, he could carve out a career.

Over the course of his work, McCurdy continues, “I came across a compound called salvia before much was published about it. I found it to be a kappa-opioid receptor antagonist and a potent hallucinogen. Years later, there was a big YouTube craze because of a video showing Miley Cyrus smoking the stuff. I was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse to study that, and I was invited by officials at NIDA to give a presentation on naturally occurring opioid compounds. I started digging into the literature and looking to see what might have been published — and that’s when I came across kratom. It was probably 2004,” when he was a staffer at the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy.

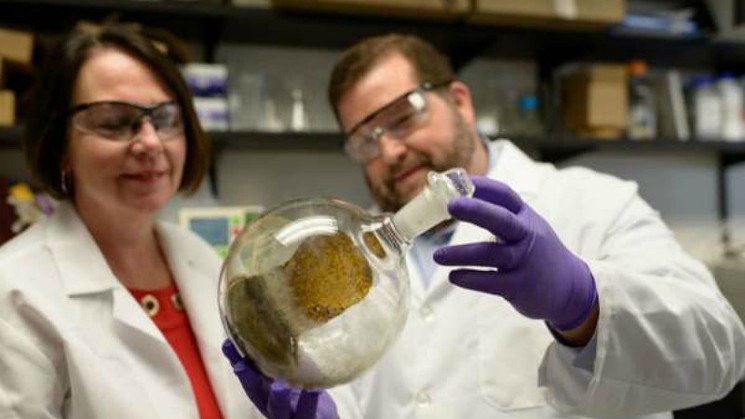

Christopher McCurdy, right, examines a flash of kratom with his late wife and fellow researcher, Bonnie Avery.

He soon realized “there was something very interesting about this plant and the alkaloids within it. It was relatively unexplored from a scientific perspective, so we didn’t know if there was any legitimacy about the claims made over the years about it either warding off withdrawals after people ran out of opiates in Thailand and Mali, where it had been traditionally used, or if it was helpful for people trying to wean themselves off illicit opioid use. I was interested in that early on.”

So, too, is Roxanne Gullikson, facility director for Portland, Maine’s Greener Pastures Holisticare, a residential treatment center that uses kratom as part of a formal and comprehensive addiction treatment regimen, as well as follow-up care. “We have counseled patients in recovery facing a surgery who are terrified of waking up with a morphine pump in their arm — afraid that it could send them back into active addiction,” she told us last year. “And this has happened. We’ve had patients tell their doctor, ‘I can’t do opiates. It would be dangerous.’ And then they wake up with pain medication connected to them. So having a supply of kratom on hand to address their pain can be very important.”

To see if he could replicate such effects, McCurdy made contact with a kratom vendor and purchased “a single batch from the same harvest — 25 kilos of leaf material that we’ve been using for about the last fifteen years. I hadn’t gotten a lot of funding at that point, but we started trying to isolate out these different alkaloids to see if they actually had analgesic activities. Were they similar to morphine? Were they less or more potent? There had only been a few papers that highlighted some of the chemistry over the years, so I wanted to replicate what was already in the literature and start understanding if these compounds had some possible treatment potential for addiction.”

Progress was slow in part because “I was basically using my own startup funds,” he explains. “I had a little support from a grant we had. But no one was really interested in kratom. They thought it was this strange thing out there and didn’t really feel there was potential behind it to study, because it was probably just another opioid, and we don’t need another opioid. That argument still goes on — but I think the real research that’s needed is going to involve humans, and that will take a long time.”

Indeed, McCurdy reveals that he tried to launch human clinical trials related to kratom way back in 2008, but “everything came to a grinding halt when they found we couldn’t say where our raw material was going to come from. That’s one of the greatest problems in advancing the research, and it’s going to be there until we can get authenticated and unadulterated kratom that hasn’t been exposed to pesticides or chemicals. These are tricky things, and having a chain of custody for that material will be problematic, because everything has to be imported into the U.S.”

True enough — and vendors have the same issue. Clean Kratom Wellness Center’s Day notes that “we are not directly importing from Indonesia. That’s illegal. We buy kratom from inside the country from companies that provide us with lab testing. But not everyone does.”

The two NIDA grants, which McCurdy describes in musical terms (“In one, we study each individual instrument, and in the other, we study the whole symphony”), have provided opportunities to get around some of these issues. For instance, he divulges, ‘We’ve started growing trees at the University of Florida. The Environmental Horticulture department is involved in this process, and we’re really starting to get an understanding of how these plants are growing, what the biochemical pathways are for synthesis, and how it can be influenced. And if we want to do a clinical product — if we can grow it from seed to commercial product — then we have a chain of custody control. That’s where I think we’re really going to make some progress and find out if we can really get to human trials. NIDA is very interested in taking mitragynine, the major alkaloid, and developing it for human clinical trials as quickly as we can, to see if it can aid with opioid cessation and trying to address the opioid crisis.”

In the meantime, McCurdy and his team are “studying the individual alkaloids within the plant, because the chain of custody doesn’t really matter in that. We’re taking leaf material or extracts we’ve purchased from various sources in the U.S., and we’re able to isolate each compound in large quantities, so we can understand how the individual alkaloids from the plant can affect an animal — rats, specifically, but we’ve also started doing some studies with beagle dogs — that’s metabolizing the compound and ultimately getting the compound out of its system. Our ultimate goal is to get this to human testing one way or another, either by purified alkaloids that can go into individual drugs, or to see if these individual compounds have real potential that can be explored and fed into some sort of standardized botanical or formulated product.”

Oliver Grundmann, another University of Florida prof, is contributing knowledge about how kratom is being consumed in America today. “He published one of the largest surveys done of kratom users,” McCurdy notes, “and the majority of them said they used it to improve mood, as well as to stay off of legal or illicit opioids — and some used it for chronic pain treatment. But there’s a huge difference between how it’s used here and how it’s used in Southeast Asia. Here, the products are all made from dried leaf material, and the drying process of the leaf is changing the chemistry and composition of the leaf. I can’t tell you exactly how or to what extent, but we’ve analyzed freshly prepared teas from Mali, and the chemical profiles are different from teas we’ve made from leaf material purchased in the U.S.”

Earlier this year, McCurdy visited Mali and saw “people picking leaves fresh off the tree. Then they’d put them into low boiling water for three or four hours until they’re reduced down, and use the tea that they brewed throughout the day, usually in 500 milliliter bottles. They’ll pour it out and use that bottle throughout the day, diluting it half and half — half juice with half warm water. And they’ll use it between three and six times a day. That’s why people compare it to coffee — because traditional use is really similar to the way we in the U.S. consume coffee or tea. And the tree itself is in the coffee family.”

Regarding charges that kratom is habit-forming, McCurdy cites java again. “In Southeast Asia, it’s socially acceptable to drink this tea, just like it is here with coffee — and they’re both addictive in that setting. If some people don’t get their coffee, they get withdrawal symptoms, and that’s pretty much what happens in Southeast Asia with mitragyna speciosa [kratom’s scientific moniker]. They get a bad feeling or a headache or something like that. But because the products are different in the U.S., that may be different, too — because it’s become a whole other beast.”

For this reason, McCurdy doesn’t fault the feds for their kratom cautiousness. “I think the FDA and the DEA [Drug Enforcement Administration] and the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] are doing what they need to be doing to protect the public. We don’t understand the science behind the products on the market. We don’t know how many of them are truly mitragyna speciosa, even though they’re labeled that way, and we don’t know how safe these products are from a bacterial or fungal or pesticide or heavy-metal standpoint. A lot of vendors are not testing these materials. They’re just buying it straight from the importer and repackaging and selling it without paying attention to any of the good manufacturing processes that are really required for botanical supplements. There’s a huge industry trying to make a buck off that because it’s the latest fad, and that’s a sad thing. Somebody has to step in and regulate the process.”

Haddow, Day and Gullikson want that, too. But McCurdy stresses that “those of us in the science field want to make sure there’s a scientific basis for any type of decisions that will be made in either making this a scheduled substance or advancing it into further human clinical research.”